"Oh, you're still painting these big girls"

"Um, yeah..."

I ran into an acquaintance a few weeks ago... My interactions with this guy feel like they're out of the pre-digital New York era. We've had great conversations about art, but I have no contact info for him. I don't even know his real name, so there's no looking him up on Facebook. I only have the pleasure of chatting with him when we physically cross paths. Anyway, I ran into him again the other day, after maybe 6 months of not seeing him. Last time we talked, I had showed him the first couple of Caitlyn paintings. He's always very encouraging about my paintings, so he asked what I'd been working on lately, so I showed him two Caitlyn paintings I currently am working on.

He connects them to the previous work, and not in any derogatory or dismissive way (he made a Jenny Saville comparison -- I'll take it!) but I still found myself stumbling over myself to talk about why I'm painting what I'm painting. I'm never great at speaking eloquently about my work, especially the body of work or particular painting(s) I'm currently in the middle of, but it's frustrating to feel like, if I can't even talk about it to someone who has shown enthusiasm for my work, how am I ever going to talk about it to an unreadable gallerist or intimidating collector.

Needless to say, I've been thinking about why I'm painting what I'm painting a lot lately.

My older work (Portland post-college work, so ~2007-10) was this sort of abstracted approach at dealing with my fears about the body. They were very deeply rooted in an effort to recover from or at least pushing back on my eating disorder and its attendant body image baggage. I hate the trope of art as therapy or art as healing, at least as far as the rationale for a professional-level body of work is concerned. (Art can be incredibly therapeutic and healing and I'm not trying to deny or dismiss that whatsoever.) But working out my baggage through paint is when I started to make work that seemed actually, objectively good and felt like mine rather than just the skilled execution of an assignment.

And then I started feeling drawn strongly to figurative work just a little before I moved to New York, where I started working from actual models. Maybe I was sick of working in isolation, me alone in my studio basement painting this anxiety-scape from inside my own head. But I still didn't know why I was making the images I was making. I'd meet with my model and shoot a bunch of reference images very loosely inspired by some visual prompt. I shot Sarah trying on a bunch of dresses she'd worn to various events; I shot Noah painting his face gold. Whatever resulted from the shoots shaped the paintings I made from them.

To be honest, I like that sense of collaboration in a process that is often by its nature very solitary. I like not having to come to the model stage with pre-established compositions sketched out, any sort of Philip Pearlstein-level staging. But maybe working with models is also an attempt to seek meaning outside myself. Not that that's a bad thing, but it switches the meaning-making process around a bit into a interpretation-of-meaning process.

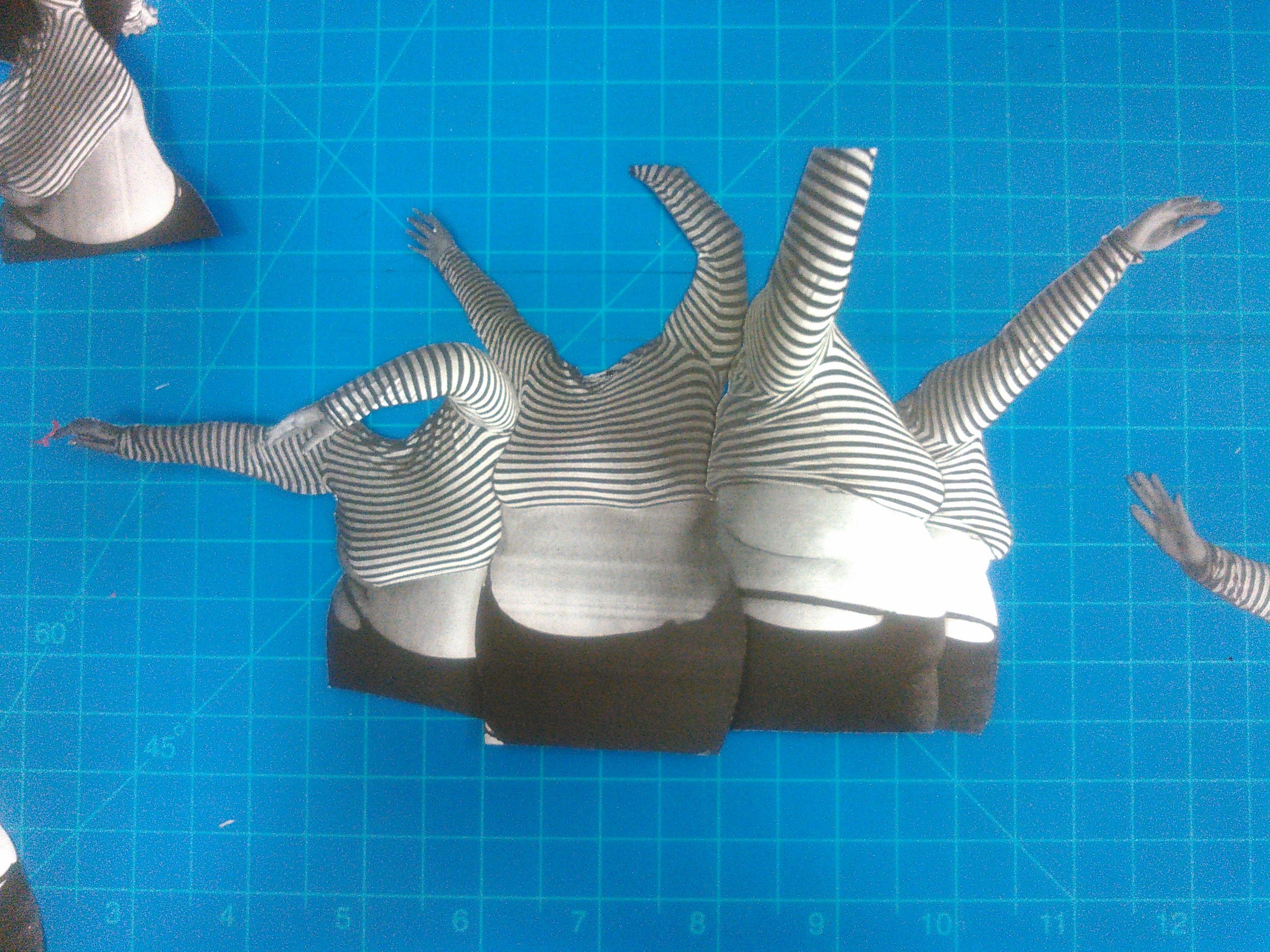

Once I have a pile of reference shots, I have to create compositions from them. Some decisions I make are purely formal. The compositions I create are what I can piece together from the pieces available to me. The paintings often seem like an obvious or inevitable outcome. But this isn't Ikea furniture; in the hands of someone else, the pieces would become something else entirely. So why am I making the choices that I am? Why am I more drawn to this pose or that image; why am I assembling them this way?

Why am I painting "the big girls?" By the time I shot Caitlyn, I had actually really been wanting to work with a plus-size model for years. But why?

In part, I can say that it's a formal choice. Thin bodies fill space differently from fat bodies. Fat bodies have folds, curves, volumes that thin bodies don't have. And fat bodies are different from what we're visually bombarded with on a regular basis. Thin bodies are the vast majority of what's visible in the media, but even figure drawing studios skew strongly that direction as well. And on the one hand, I get it. An athletic body with relatively low body fat and relatively defined musculature is a great way to learn the construction of the body as it is relevant to creating figurative art. Bony landmarks, muscle placement: of course they're easier to see under lean, un-marked skin. But ultimately, they're only an idealized specimen that doesn't much represent the full rainbow of human bodies.

I think my desire to work with a plus-sized figure was, at least initially, a continuation of my more abstract work, attempting to exorcise my anxieties about the body. About my own body. But the more I work with these images, and even as I'm thinking about who I want to work with next, I think maybe what I'm trying to do is create a world in which all bodies are worth painting. In which all bodies are worth seeing, are valid, are interesting.

I hesitate to say "beautiful" because my thoughts on whether a painting -- or a body, for that matter -- must be beautiful in order to be "good" or worthwhile is a whole separate rant. And it's also worth noting that the act of wondering why I'm making the images isn't keeping me from going ahead and making them. I'll make what I feel drawn to make, and figure out what it means along the way.